GEOFFREY COBB

Author, “Greenpoint Brooklyn’s Forgotten Past

gcobb91839@Aol.com

The other night I met James Nunez, a lifelong Greenpointer of Puerto Rican heritage and we reminisced about the long history of Puerto Ricans in North Brooklyn. Though Puerto Ricans still comprise a vibrant part of our community, many have been forced out of our area, victims to gentrification. James’ grandmother ran a Puerto Rican restaurant in the area until the 1990s. When I first arrived in Greenpoint in the early 1990s, walking north of Greenpoint Avenue meant experiencing Puerto Rico’s exuberant culture. Families sat outside on the street often playing dominoes while listening to salsa music, the smell of pork or chicken being barbecued on a grill wafting through the air.

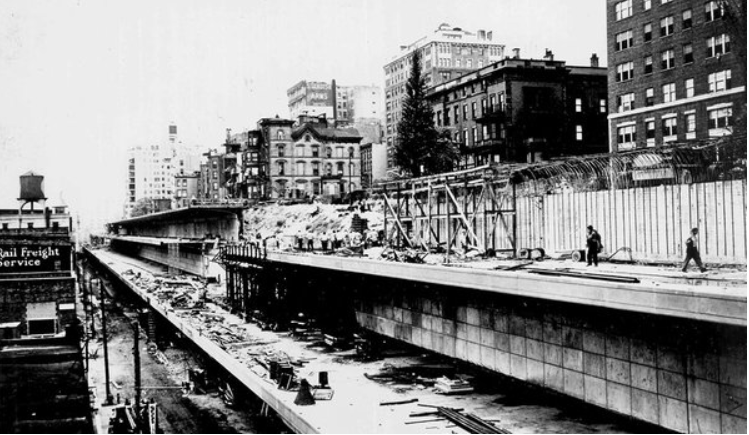

Many North Brooklyn residents are surprised to learn that Puerto Ricans have lived in our area for over a century. In 1924, Congress passed the first immigration law, severely restricting immigration by establishing national quotas based on the 1890 census, heavily favoring Northern and Western Europeans, and completely barring Asians, particularly Japanese, reflecting widespread nativism and xenophobia. This act dramatically reduced overall immigration, created the first U.S. Border Patrol, and aimed to preserve a perceived homogeneous “American” demographic makeup for decades. In the 1920s, North Brooklyn was the beating heart of industrial New York City, then the planet’s largest industrial city. Local factories, heavily dependent on immigrant Jewish, Polish and Italian labor, facing a manpower shortage, looked to Puerto Rican whose residents were American citizens legally able to work in New York.

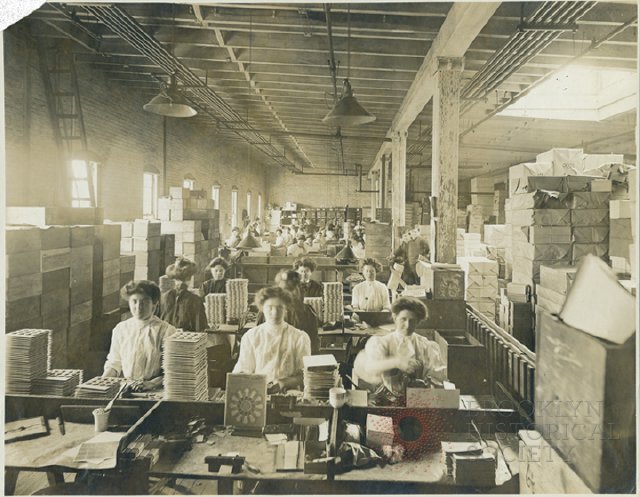

One of the local industries hit was the by the labor shortage was the American Hemp Rope Manufacturing Company located on a sprawling campus on West Street. Desperate for workers, the firm sent a ship to Puerto Rico and returned with 130 Puerto Rican women to make rope and shoelaces for the company Other local industries also recruited workers in Puerto Rico including Domino Sugar, which once ran the world’s largest sugar refinery in Williamsburg.

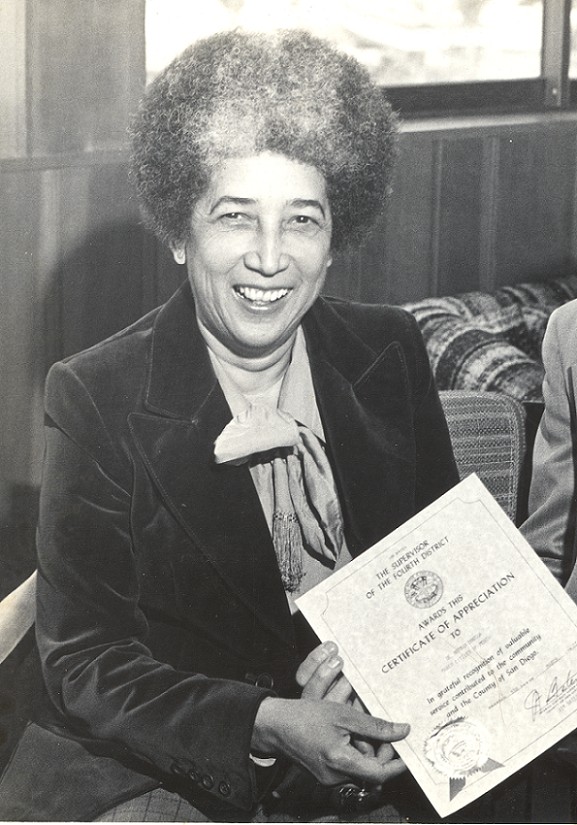

Puerto Ricans who spoke Spanish as a first language encountered many problems, including racism, discrimination and language issues because local schools for many years had no programs for immigrant children to learn English as a second language. Puerto Rican children suffered a very high dropout rate in schools. In 1961, Puerto Rican woman Antonia Pantoja founded ASPIRA (Spanish for “aspire”), a non-profit organization that promoted educational reform to help struggling Hispanic students. In 1972, ASPIRA of New York, filed a federal civil rights lawsuit demanding that New York City provide classroom instruction for struggling Latino students and bilingual and English as a Second Language instruction was born helping Hispanic students learn English and stay in school.

By the 1950s, North Brooklyn had become home to thousands of Puerto Rican migrants. Many white residents left Brooklyn in the 1960s for the suburbs and Puerto Ricans quickly replaced them. The North end of Greenpoint became predominately Puerto Rican and the south side of Williamsburg also grew into a huge Puerto Rican quarter.

By the late 1960s, Puerto Ricans comprised about a third of the local population. Many Puerto Ricans bought houses left by locals fleeing the area for the suburbs and a generation of Puerto Rican Greenpointers came of age locally. Although some Puerto Ricans owned their own homes most were renters who were forced out by rising housing prices.

Puerto Ricans soon organized to fight gentrification. In 1972, Puerto Ricans and other Hispanics in the south side of Williamsburg helped organize Los Sures, a community organization that still exists, which fights to help working-class people secure their housing rights. Los Sures was also perhaps the first North Brooklyn organization to provide a number of vital community services including education, senior citizen services and even a food pantry. Los Sures began responding to problems that confront tenants today, including withdrawal of city services, lease violations and illegal evictions. The organization also fought property owners trying to vacate their buildings to gentrify and whiten the neighborhood. Los Sures promoted community-based control of housing, both through management and ownership. In 1975, Los Sures became Brooklyn’s first community-based organization to enter into agreements to manage City-owned properties. It also became one of the first tenant advocacy groups to undertake large-scale rehabilitation. Still fighting for local people, Los Sures is a vital force in community activism.

Though the Puerto Rican presence in North Brooklyn is far smaller than it once was, many Puerto Ricans still and work in our area. Many Puerto Rican Greenpointers run local businesses including lifelong resident Catherine Vera Milligan who runs a wonderful coffee shop at 269 Nassau Avenue. If you want to eat delicious authentic Puerto Rican food try Guarapo restaurant on 58 North 3rd Street, Chrome at 525 Grand Street or La Isla at 293 Broadway. These places prove that Puerto Rican culture is still a vital part of the gorgeous mosaic of cultures that make up North Brooklyn. The other night I met James Nunez, a lifelong Greenpointer of Puerto Rican heritage and we reminisced about the long history of Puerto Ricans in North Brooklyn. Though Puerto Ricans still comprise a vibrant part of our community, many have been forced out of our area, victims to gentrification. James’ grandmother ran a Puerto Rican restaurant in the area until the 1990s. When I first arrived in Greenpoint in the early 1990s, walking north of Greenpoint Avenue meant experiencing Puerto Rico’s exuberant culture. Families sat outside on the street often playing dominoes while listening to salsa music, the smell of pork or chicken being barbecued on a grill wafting through the air.

Many North Brooklyn residents are surprised to learn that Puerto Ricans have lived in our area for over a century. In 1924, Congress passed the first immigration law, severely restricting immigration by establishing national quotas based on the 1890 census, heavily favoring Northern and Western Europeans, and completely barring Asians, particularly Japanese, reflecting widespread nativism and xenophobia. This act dramatically reduced overall immigration, created the first U.S. Border Patrol, and aimed to preserve a perceived homogeneous “American” demographic makeup for decades. In the 1920s, North Brooklyn was the beating heart of industrial New York City, then the planet’s largest industrial city. Local factories, heavily dependent on immigrant Jewish, Polish and Italian labor, facing a manpower shortage, looked to Puerto Rican whose residents were American citizens legally able to work in New York.

One of the local industries hit was the by the labor shortage was the American Hemp Rope Manufacturing Company located on a sprawling campus on West Street. Desperate for workers, the firm sent a ship to Puerto Rico and returned with 130 Puerto Rican women to make rope and shoelaces for the company Other local industries also recruited workers in Puerto Rico including Domino Sugar, which once ran the world’s largest sugar refinery in Williamsburg.

Puerto Ricans who spoke Spanish as a first language encountered many problems, including racism, discrimination and language issues because local schools for many years had no programs for immigrant children to learn English as a second language. Puerto Rican children suffered a very high dropout rate in schools. In 1961, Puerto Rican woman Antonia Pantoja founded ASPIRA (Spanish for “aspire”), a non-profit organization that promoted educational reform to help struggling Hispanic students. In 1972, ASPIRA of New York, filed a federal civil rights lawsuit demanding that New York City provide classroom instruction for struggling Latino students and bilingual and English as a Second Language instruction was born helping Hispanic students learn English and stay in school.

By the 1950s, North Brooklyn had become home to thousands of Puerto Rican migrants. Many white residents left Brooklyn in the 1960s for the suburbs and Puerto Ricans quickly replaced them. The North end of Greenpoint became predominately Puerto Rican and the south side of Williamsburg also grew into a huge Puerto Rican quarter.

By the late 1960s, Puerto Ricans comprised about a third of the local population. Many Puerto Ricans bought houses left by locals fleeing the area for the suburbs and a generation of Puerto Rican Greenpointers came of age locally. Although some Puerto Ricans owned their own homes most were renters who were forced out by rising housing prices.

Puerto Ricans soon organized to fight gentrification. In 1972, Puerto Ricans and other Hispanics in the south side of Williamsburg helped organize Los Sures, a community organization that still exists, which fights to help working-class people secure their housing rights. Los Sures was also perhaps the first North Brooklyn organization to provide a number of vital community services including education, senior citizen services and even a food pantry. Los Sures began responding to problems that confront tenants today, including withdrawal of city services, lease violations and illegal evictions. The organization also fought property owners trying to vacate their buildings to gentrify and whiten the neighborhood. Los Sures promoted community-based control of housing, both through management and ownership. In 1975, Los Sures became Brooklyn’s first community-based organization to enter into agreements to manage City-owned properties. It also became one of the first tenant advocacy groups to undertake large-scale rehabilitation. Still fighting for local people, Los Sures is a vital force in community activism.

Though the Puerto Rican presence in North Brooklyn is far smaller than it once was, many Puerto Ricans still and work in our area. Many Puerto Rican Greenpointers run local businesses including lifelong resident Catherine Vera Milligan who runs a wonderful coffee shop at 269 Nassau Avenue. If you want to eat delicious authentic Puerto Rican food try Guarapo restaurant on 58 North 3rd Street, Chrome at 525 Grand Street or La Isla at 293 Broadway. These places prove that Puerto Rican culture is still a vital part of the gorgeous mosaic of cultures that make up North Brooklyn.