By Cole Sinanian

A lunch guest at the Fifth Avenue Hotel in Madison Square at the turn of the 20th century could’ve ordered their oysters however they desired. The menu offered the supposed aphrodisiac in virtually every way it could conceivably be prepared: Raw, stewed, fried, broiled, Baltimore broiled, cocktail, steamed, Boston stewed, box stewed, cream broiled, roasted on shell, roasted on toast, a la poulette…

In a city of pizza, halal, bagels and Michelin stars, the oyster’s special place in New York gastronomy may seem an afterthought today. But not long ago it was ubiquitous as lamb over rice or a summer hot dog in the park. In the late 1800s, Delmonico’s restaurant was serving local oysters on its dinner menu. In colonial times, locals were pulling enormous oysters from the muck of Gowanus creek to be canned, pickled with allspice, vinegar, and nutmeg, and exported throughout the colonies. Also on Delmonico’s dinner menu: a stew of terrapin meat (a small marsh turtle) simmered with cream and Madeira wine. It was among the historic restaurant’s priciest dishes, costing what today would have been $75. According to New York Public Library’s “What’s on the menu” project, a more traditional Lenape-style terrapin, which is roasted over an open fire, was a cheaper alternative that was once common in the city’s taverns.

Two perhaps bizarre sources of protein by today’s standards, the terrapin and the oyster earned their place on the menus of the city’s most exclusive restaurants through sheer abundance. Long before the tangle of cranes, bridges, towers and container ports clogged the horizon, New York Harbor was a lush estuarine paradise. The story of Henry Hudson’s first sighting of New York Harbor in 1609 is well known: Upon entering the bay in his ship, the Half Moon, he saw breaching whales, otters, enormous schools of fish, rays, turtles, and tens of millions of oysters arranged in vast, stony oyster reefs. They were huge, some up to a foot long, and so plentiful they could be plucked like fruit from the shallow brackish water.

The Lenape had done this for thousands of years. Resource-wise, they were maybe the richest of North America’s First Peoples. They grew corn, beans, and squash from Mesoamerica. They picked wild fruits and berries from the lush deciduous forest of their Northeast woodland home. They collected eggs, nuts and acorns, and hunted forest animals for meat. They spearfished for eel, herring and bony fishes of all sorts. And of course they harvested the oyster beds to their stomachs’ content. There were 220,000 acres of oyster beds in New York waters at the time of Hudson’s arrival, which, by some estimates, constituted half of all the oysters on planet Earth.

But the abundance was short-lived. Colonization brought about rapid industrialization and drove nearly all the Lenape from their ancestral homelands. Yet native traditions endured, oyster-eating among them. New York’s population exploded, breaking 100,000 by the early 1800s, and everyone, it seemed, was addicted to oysters.

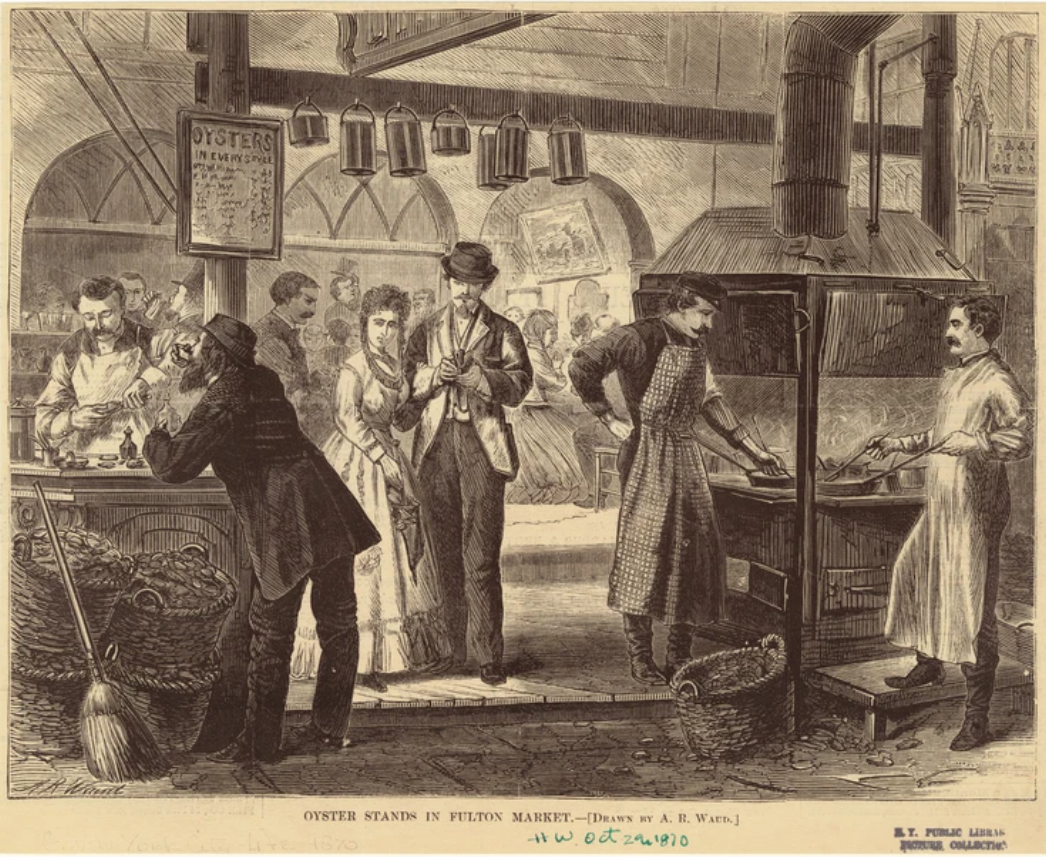

In the book, “Gowanus: Brooklyn’s Curious Canal,” by Joseph Alexiou, a Dutch missionary named Jasper Danckaerts describes pulling giant oysters from the Gowanus Creek. The oysters are “large and full, some of them not less than a foot long, and they grow sometimes ten, twelve and sixteen together” Oyster stalls and taverns began popping up everywhere. They made their way into the cityscape. Trinity Church was built with a paste of crushed oyster shells. Pearl Street owes its name to them. They were early New York City’s preferred street food. Mark Kurlansky details this in his 2006 book, “The Big Oyster”: “Before the 20th century, when people thought of New York, they thought of oysters,” he wrote. “This is what New York was to the world—a great oceangoing port where people ate succulent local oysters from their harbor.”

This, of course, was unsustainable. By the early 1900s, the shellfish had gone scarce. Nearly a billion oysters were being harvested from New York waters each year. Meanwhile, the oysters that remained were sick with pollution. The last New York oyster beds were closed in the 1920s. Now, the Gowanus is filled not with oysters but foul smelling “black mayonnaise.”

Under the relentless forces of capitalism and industrialization, the Lenape were dispossessed of their waters and the waters of their oysters. Terrapins, too, have been listed as “vulnerable” to extinction by the IUCN. But there’s hope for New York’s oyster and turtle lovers. Terrapins have been making a comeback. In 2011, dozens of the reptiles migrating from Jamaica Bay caused delays at JFK. And oysters have once again found a friend among humans. The Billion Oyster Project has restored some 150 million oysters to New York waters to help prevent flooding and erosion. In 2018, a group called the River Project found an oyster that was 8.6 inches long and nearly two pounds, the largest recovered in more than a century. Although it may be another century before New York’s oysters are edible again.